Underdog bias rules everything around me

They're just as scared of us as we are of them

People very often underrate how much power they (and their allies) have, and overrate how much power their enemies have. I call this “underdog bias”, and I think it’s the most important cognitive bias to understand in order to make sense of modern society.

I’ll start by describing a closely-related phenomenon. The hostile media effect is a well-known bias whereby people tend to perceive news they read or watch as skewed against their side. For example, pro-Palestinian students shown a video clip tended to judge that the clip would make viewers more pro-Israel, while pro-Israel students shown the same clip thought it’d make viewers more pro-Palestine. Similarly, sports fans often see referees as being biased against their own team.

The hostile media effect is particularly striking because it arises in settings where there’s relatively little scope for bias. People watching media clips and sports are all seeing exactly the same videos. And sports in particular are played on very even terms, where fairness just means enforcing the rules impartially.

But most possible conflicts are much less symmetric, both in terms of what information each side has, and even in terms of what game each side is playing. Consider, for instance, an argument about whether big corporations have too much power. The proponent might point to corporations’ wealth, employee talent, and lobbying ability; their opponent might point to how many regulations they have to follow, how much corporations compete between themselves, and how strong anti-corporate public sentiment is. In order to evaluate a question like this, people need to decide both how to draw coalition boundaries (to what extent should big corporations be counted as a single unified group?) and how to weigh different types of power against each other.

I think that biases in how these weighings and boundaries are evaluated are a much bigger deal than biases in evaluating fairness in isolated contexts. Specifically, I think that people typically underrate the types of power they have, and overrate the types of power their opponents have. You’re intimately familiar with the limitations of your own abilities—you run into them regularly, often in deeply frustrating ways. You track all the fractures inside your own coalition, and they often seem fundamental and intractable. Conversely, it’s easy to forget about the things which are much easier for you than for your opponents, and to view their internal rivalries as temporary and easily-resolved.

These effects are exacerbated by information asymmetries, aka the “fog of war”. You know who’s working with you; you don’t know who’s working against you. When outside observers sympathize with your side, you know that they’re not actually contributing very much to your cause; when outside observers sympathize with your opponents, you don’t know if that’s a sign of enmity. Similarly, you know how your own plans are progressing, but you don’t know what your opponents are scheming. To see how strong this effect can be, just look at fiction, where villains often implement arbitrarily-complicated schemes offscreen without breaking suspension of disbelief.

In addition to the hostile media effect, underdog bias is related to a number of other biases (like hostile attribution bias, siege mentality, the fundamental attribution error, and simple tribalism). But hopefully the description above conveys why I think it’s fundamental enough to be worth separating out.

Underdog bias in practice

In this section I give six examples of conflicts where each side thinks (with some justification) of themselves as the underdog, and rejects the idea of their opponents being the underdogs. I won’t try to defend them in detail, but they hopefully convey the pervasiveness of underdog bias.

Government vs industry

Working within a government is often a miserable experience. Government institutions are typically cash-strapped and unable to hire the most talented people; meanwhile they face heavy opposition from industry, which can spend enormous amounts of money lobbying, donating to candidates, etc. Many employees at regulatory agencies see themselves as underdogs trying to rein in whole industries, while working under strong political and bureaucratic constraints.

Big corporations have a lot of money, but are in a constant state of cut-throat competition, and also need to comply with a huge number of regulations. Bureaucrats can very easily make their lives harder in ways ranging from trivial (e.g. adding red tape) to existential (e.g. blocking acquisitions). So it’s easy for companies to feel like underdogs pitted against the power of the state—especially when it seems like exercises of that power might be influenced by their competitors.

Tech vs media

Many journalists see themselves as underdogs fighting the accumulation of power by special interests, of which tech is the most prominent. This feeling is exacerbated by how financially precarious the industry is. The rise of social media has decimated newspaper jobs, leading newspapers to optimize far harder for engagement than they used to.

The tech industry has huge amounts of money, and the ability to reshape the world in many ways, but has historically wielded relatively little cultural and political influence. Many techies see themselves as underdogs fighting the cultural establishment, as exemplified by a pervasive (and often extreme) anti-tech bias in the news media. Techies (until recently) have felt like nobody represents their interests in DC, where both Democrats and Republicans have historically been anti-innovation.

Elites vs masses

Normal people view themselves as underdogs in a world where cultural elites (e.g. top university graduates) control almost all major institutions. Even when they vote for outsiders, the effects of those elections are blunted by elite control over institutions (especially the “deep state”). Elite ideology has increasingly diverged from the ideology of the masses, making many people feel helpless to elect anyone who will actually represent their interests.

Cultural elites control almost all major institutions, but are few in number. Elites feel scared of populist masses who distrust them, and who can vote for anti-elite candidates. The most elite groups (like billionaires or Jews) are often the ones it’s most socially acceptable to blame for problems, or even call for violence against.

Republicans vs Democrats

Many Republicans see themselves as underdogs fighting against the Democratic elites who have far more influence within universities, government bureaucracies, legacy media outlets, and tech companies. They see themselves as fighting against pervasive ideological control over a wide range of institutions.

Many Democrats view Republicans as having structural advantages—such as the Electoral College, or the Senate—which allow them to remain competitive even with fewer supporters. Democrats therefore view themselves as underdogs fighting for change against existing cultural norms and Republican-run power structures (like the Supreme Court).

America vs China

America has more power in the sense of established hegemony. China has more power in the sense of momentum and, increasingly, manufacturing and economic superiority. The likelihood of conflict between a rising power (who’s worried about overcoming their historical disadvantage) and an established power (who’s worried about their opponents’ growth trajectory) is known as the Thucydides trap.

Israel vs Palestine

Many Palestinians see themselves as underdogs against an opponent with far more military power than them, which is also strongly backed by the US.

While Israel has power over Palestine specifically, it’s also surrounded by hostile neighbors far larger than it, which have often stated their intention (and repeatedly actually tried) to wipe Israel off the map. Many Israelis see themselves as underdogs who have to defend themselves against an entire region (as well as increasingly-hostile public opinion in the west).

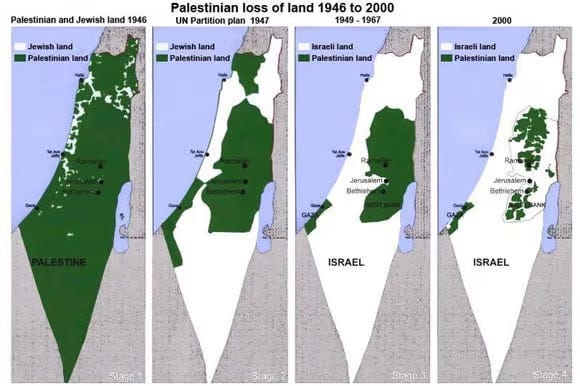

The two maps below are sometimes shown by supporters of each side as a way of conveying how much of an underdog their side is. (To be clear, I’m not endorsing either of them, just illustrating the rhetorical strategies being used.)

Underdog bias doesn’t imply that any of these groups are wrong to be scared of their opponents’ power. But it does suggest that they’ll tend to underestimate their own power and, crucially, underestimate how scared their opponents are of them. (The applications of this principle to the politics of AI are left as an exercise for the reader.)

Why underdog bias?

If underdog bias makes us so wrong about the world, why is it such a strong psychological effect? Some cognitive biases are just clear-cut mistakes, but we should expect that the strongest “biases” were evolutionarily adaptive in some way.

The descriptions I gave above suggest that there are qualitative differences in the types of reasoning about ourselves and our enemies—roughly corresponding to near vs far mode. In near mode we focus on concrete, nuanced details about our local situation. In far mode, we construct larger-scale narratives, in more black-and-white terms, often for the sake of signaling to others.

Why might signaling that you’re the underdog be more important than having accurate beliefs? One possibility is to gain allies. Vandallo et al. have a few studies on the effects of appearing to be the disadvantaged side. Scott Alexander summarizes their conclusions as follows: “if you get yourself perceived as the brave long-suffering underdog, people will support your cause and, as an added bonus, want to have sex with you”. And in this post he points to the longstanding prevalence of underdogs in narratives (stretching back to myths like that of David and Goliath).

But he also recognizes that there’s a big difference between reported and actual support. All else equal, underdogs are pluckier and their victories more impressive—so it makes sense that we support them on a narrative level, when there’s no cost to doing so. But in real life supporting the underdog means that you’re on the side most likely to lose. Whether or not underdog bias is beneficial for gaining allies will therefore depend on whether those allies are more concerned about being (or looking) virtuous, or more concerned about actually winning. And while the modern era is dominated by virtue signaling, that was much less true in the ancestral environment, where resources were much scarcer. In that setting you’d instead expect people to have “overdog bias” which makes them overestimate their own side’s strength (which is one way that tribalism, patriotism, etc. can be interpreted).

Another possibility is that underdog bias is most valuable as a way of firing up your own supporters. I see this in action whenever I accidentally give my email to a political candidate, and get bombarded with emails about how I need to donate because the other side is on the verge of an overwhelming victory. But again, there’s a missing link: why should fear make you fight harder? On a rational agent model, being the underdog could make you decide fighting isn’t worth it—or even make you defect to the enemy. And on an emotional level, being scared makes it much harder to think clearly or navigate complicated situations.

So my best guess is that underdog bias was useful because ancestral conflicts were simple and compulsory. In other words, our political intuitions are calibrated for a world where alliances are more tribal—where we don’t have freedom of movement or freedom of association. People used to be stuck with their family/tribe/ethnic group whether they liked it or not; if they tried to ally with another, they were often rejected, or at best permanently viewed as an untrustworthy outsider. So the only rational response to being in a worse position would be to fight harder, using fairly straightforward and intuitive strategies.

In one way, this response is maladaptive in the modern world—where fewer battle lines are based on immutable characteristics or irreconcilable differences, and the best way to approach conflict is less intuitive. Yet as I mentioned above, the modern world is also much more sympathetic to victims. This suggests that underdog bias may have gradually transitioned from a way of firing up one’s supporters, to something closer to a victim complex aimed at evoking sympathy from onlookers.

This whole section has been very speculative, and I’m still not confident in my answer to where underdog bias comes from. But we don’t need an explanation of underdog bias to believe that it corrupts many people’s thinking about complex issues. How can you actually reduce your underdog bias, though? The best approach I’ve found is simple in theory (though devilishly difficult in practice). Say to yourself: “they're just as scared of us as we are of them.” It’s true far more often than you think.

Your post has very good insights, but when push comes to shove, Osama bin Laden correctly observed that "When people see a strong horse and a weak horse, by nature they will like the strong horse."

Idk if this is anything, but assuming you're going to fail can be a good corrective to natural laziness / overconfidence / un-thoroughness, so maybe it's adaptive to turn this on in high stakes circumstances as a kind of instinctive pre-mortem.